NOISE: THE MESSAGE IN THE INFORMATION SOCIETY

What is social noise?

You read more. You watch videos, you listen to more podcasts than ever. And yet you know nothing.

And you keep publishing. Posts, stories, threads, articles. You document every experience, every thought, every moment. And yet nobody really sees.

For millennia, information was an exchange. Reading meant gathering knowledge, entering other symbolic worlds. Speaking meant transmitting meaning. There was symmetry: those who spoke knew they were being heard. Those who listened chose what deserved attention.

Information was rarefied, incomplete, still to be processed. Just think how difficult it was 20 years ago to find song titles, scientific papers, historical documents.

Today? Today you produce and receive 650 million pieces of content a day. Scroll. Like. You publish without knowing if anyone will read. You share without reading deeply. You react without checking. At the end of the day you haven’t learned anything that will change your thinking. And no one has really read what you wrote.

The problem isn’t that you read too little or publish too much. It’s that you do both compulsively and nothing has weight – or the right weight.

You’ve gone from seeker of knowledge to processor of noise. From transmitter of meaning to producer in the void. Information is no longer an exchange between humans. It’s an algorithmic flow that passes through us — in and out — without ever settling.

Does it still make sense to publish when no one reads? Does it still make sense to read when everyone publishes? Or better: why do you keep doing both even when you know it’s pointless?

To answer, we need to understand what happened to the very structure of information.

THE STRUCTURE OF EXCLUSION

In the 1990s, while everyone was celebrating the Internet as the democratization of knowledge, Manuel Castells saw something else: the rise of the Information Society.

In The Rise of the Network Society he describes a social paradigm shift where power derives from controlling information flows. Two structural principles govern this new reality.

First: time has collapsed. Events that would require days now have to be analyzed in minutes. Reaction replaces judgment. Urgency becomes permanent. You don’t have time to process what you read. You don’t have time to curate what you publish.

Second: physical space loses relevance. Your information community is no longer territorial, it’s algorithmic. You publish for an audience you don’t see. You consume content from sources you don’t know.

But Castells goes further. He identifies a devastating consequence: the network society structurally produces extreme inequalities. Not gradual. Exponential.

THE MATHEMATICS OF NETWORKS (DIGITAL AND SOCIAL)

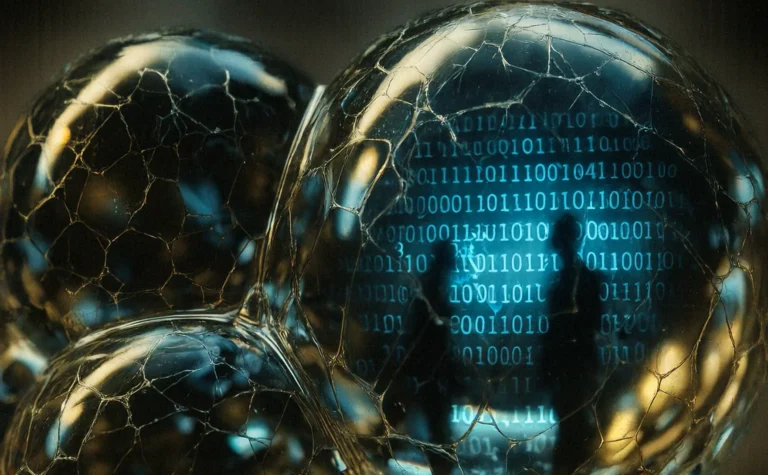

In Linked, Albert-László Barabási mathematically demonstrates what Castells described: in information networks, “power laws” dominate — power-law distributions that exponentially amplify social dynamics.

In normal distributions, values are fairly uniform, with most clustered around the average. In power-law distributions, values are highly asymmetric: the vast majority near the minimum, a few at the maximum.

It’s a perfect snapshot of digital reality:

Web: 1% of sites receive 99% of traffic

Social: 1% of accounts generate 90% of interactions

X: 10% of users produce 92% of visible content

Instagram: 5% of creators receive almost all engagement

LinkedIn: 1%

This is not just social injustice (even though it is). It’s a mathematical property of networks.

Barabási identifies the precise mechanism: preferential attachment. When a new node enters the network, it connects preferentially to nodes that already have many connections. The algorithm amplifies whoever is already visible. Those who start invisible stay invisible. No second chances. Only exponential feedback loops.

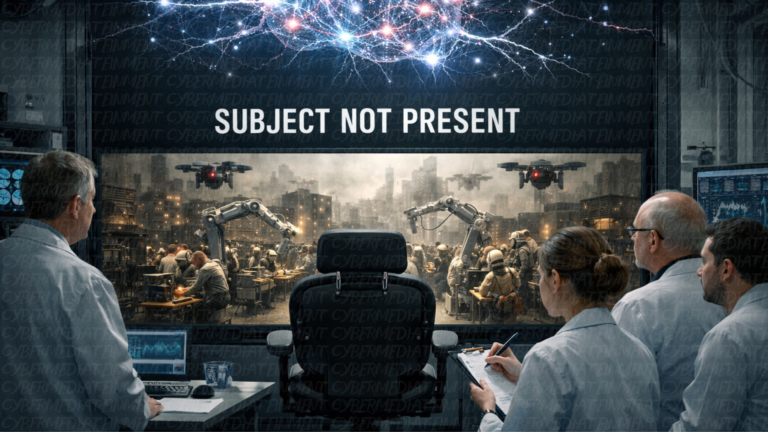

And you? Statistically, you are the invisible node. Both when you produce and when you consume.

When you produce: the algorithm favors accounts that already have visibility. Your content — no matter how brilliant — starts invisible and stays invisible.

When you consume: the algorithm keeps showing you the same dominant nodes. You see the usual creators, the usual brands, the usual voices. The informational diversity the network promises is an illusion.

Robert K. Merton had already identified this phenomenon in the 1960s with the term Matthew Effect: “to those who have, more will be given; from those who have not, even what they have will be taken away.” In digital networks, the effect is amplified by orders of magnitude.

THE ATTENTION ECONOMY

In 1971 Herbert Simon wrote: “in an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is the attention of its recipients.”

Here is the paradox of the attention economy: production destroys value. The more content exists, the more attention fragments, the less visibility each single piece receives, the more you have to produce to hope to be seen. Vicious circle.

The information society produces information in pathological abundance but less and less knowledge. Knowledge requires time, sedimentation, context. It requires stepping out of the flow.

But you can’t step out. If you exit the flow as a producer, you become invisible. If you exit as a consumer, you are cut off.

Neil Postman: information becomes disinformation when it is detached from context, history, and the possibility of action. You don’t just receive fake news. You receive too many fragmented, decontextualized, unusable pieces of information. And you produce the same: content without context, reactions without reflection.

NOISE

Daniel Kahneman in Noise (2021) gives us a clear definition of noise as “undesirable variability in judgments that should be identical.” Formula: Error² = Bias² + Noise². Even if you completely eliminate bias, if you keep high variance in judgments, the error remains huge. In overloaded systems, noise dominates.

On social media, our perceptual apparatus is permanently overloaded. As a producer: you don’t know what will work, what will be seen, what will have impact. As a consumer: judgment is unstable, evaluative capacity is exhausted.

You can’t distinguish what is important. Not for lack of skill. But because the sheer volume makes distinction structurally impossible.

Noise is not a bug. It is the emergent property of a system that has exceeded human cognitive capacity.

650 million new pieces of content. Every day. On Instagram, TikTok and X alone.

At best, your brain can deeply process one, maybe two pieces of content per second. The system produces at a speed that exceeds your cognitive capacity by two orders of magnitude.

You no longer read. You scroll. You don’t understand. You absorb. You don’t reflect. You react. And you don’t publish to communicate. You publish to prove that you exist.

The more you consume, the less you know. Each piece of content erases the previous one. No sedimentation, no integration, no cumulative understanding.

The more you produce, the less impact you have. Every post is lost in the stream. Every idea is buried. No accumulation of reputation, no building of authority, no organic growth.

Why do we keep going?

SOCIAL NOISE AND COMPULSION

And yet you can’t stop. Neither publishing nor reading.

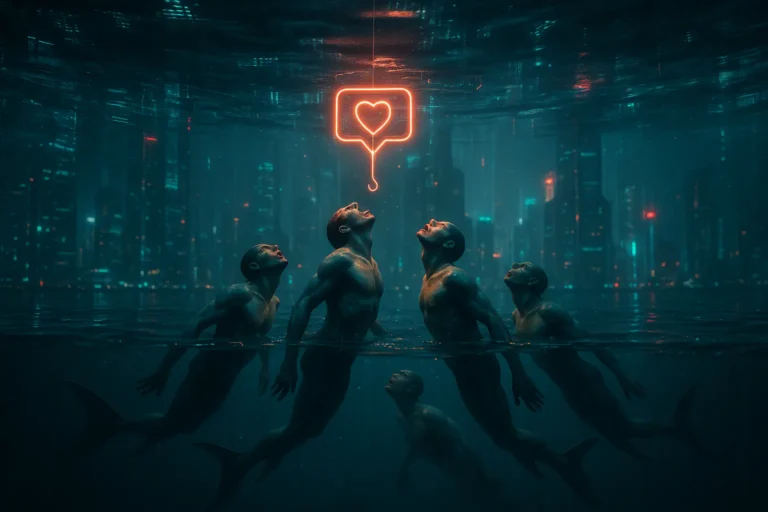

Maurizio Ferraris in Documentalità (2012): “to exist means to leave documentary traces.”

An event that is not documented has not happened. An experience that is not posted has not been lived. A thought that is not shared does not exist. But there is a second imperative: if you are not informed, if you don’t know the trend, you are cut off.

You no longer read to understand. You read to exist socially. You no longer publish to communicate. You publish to prove that you exist.

Two compulsions. One structure. Same mechanism.

If you are not trackable — as producer AND as consumer — you are not social. And in a society structured as a network, this means expulsion. Invisibility equals non-existence.

Sherry Turkle gave this effect a name: Fear Of Missing Out. But FOMO in the information society is not an individual pathology. It is a rational response to a structural incentive. It applies both to consumption and production.

The only way to avoid it: stay permanently connected. Check compulsively. Scroll, publish without stopping.

You don’t know what you will find when you scroll. You don’t know who will see your post. Variability is maximum on both fronts. Like a slot machine: you keep going hoping that this time it will really be worth it. That this post will blow up. That this scroll will bring something valuable.

It almost never happens. But it happens just often enough to sustain the behavior. It’s the variable ratio reinforcement schedule. B.F. Skinner demonstrated it in the 1950s with pigeons. We experience it voluntarily. As producers and as consumers.

Self-Exploitation as Freedom

Byung-Chul Han in Psychopolitics (2014) describes the final consequence: the feeling of structural uselessness disguised as freedom.

You are not failing as a creator because you’re not good enough. You are not failing as a reader because you’re not intelligent. The system is designed this way. But the system makes you believe it’s your fault.

Han calls this “optimized self-exploitation”: the system convinces you that you are responsible for your visibility AND your information. But you are just a node in a network that extracts value from you (attention, data, time, cognitive energy, content) without returning either real knowledge or real visibility.

No one forces you. You choose to open the feed. You choose to scroll, to publish. But is it really a choice?

MIMETIC AND RATIONAL

Individually, staying informed is rational. Individually, interacting, publishing and staying visible is rational.

But collectively? The more everyone produces, the less each person is seen. The more everyone consumes, the less each person understands.

Garrett Hardin described this dynamic in the 1960s: the “tragedy of the commons”: a common, freely accessible resource is over-exploited. Every rational individual maximizes their own use. The benefit is immediate and personal. The cost — the degradation of the resource — is distributed across everyone.

It’s a suboptimal Nash equilibrium: rational individual choices produce disastrous collective outcomes. We would all be better off if we produced and consumed less. But no one can afford to be the first to disconnect. You would fall behind as a reader.

We are trapped in an informational prisoner’s dilemma where the only rational move is to keep playing — compulsively producing and consuming content — even knowing the game is rigged.

SOCIAL NOISE: NO WAY OUT

Does it still make sense to publish? Does it still make sense to engage online and stay informed?

No. Mathematically no. Cognitively no. Rationally no.

And yet we keep doing both. Because the system has convinced us that the alternative — exiting the networks, digital silence, informational disconnection — equals social death.

We keep publishing because the alternative — invisibility, exclusion, silence — terrifies us more than futility does. Individual rationality produces collective irrationality. We are simultaneously producers, consumers, and products in an ecosystem that cannot work and yet cannot stop.

We live in a society where the exchange and creation of information is both useless and mandatory.

Only simulation of connection. Only performance of existence. Only compulsive production and consumption of noise to prove to ourselves that we are still here, that we still know something, that we still exist, that someone still sees us.

We keep producing in the void and reading in the noise knowing it won’t make sense, hoping that maybe this time something will really change. That someone will see. That something will have weight.

It won’t happen.

Noise is not a bug. It is the system.

© CYBERMEDIATEINMENT 2025

#FOLLOWTHEALGORITHM